Matthew Picton at SolwayJones

by Tucker Neel

Originally published in Artillery Magazine jul/aug 2009 vol. 3

Cities are living creatures, shifting and growing, contracting with time, but fragile too, subject to the forces of historical change and destructive powers both internal and external. This fact is no more evident than in Matthew Picton’s recent exhibition “Postwar Landscapes” at SolwayJones. Here, Picton presents five works that deploy the formal tropes of mapping to speak to memories of space and time.

In one of the most alluring works, Moscow 1808, 1905, 2007, 2008, Picton traces Moscow city maps from these four years in white-painted Duralar and pins them, like preserved scientific specimens, atop each other against a black background. The ghostly sinewy lines of rambling city streets attest to a place that congeals and expands its borders and features. It is up to the viewer to give the work’s four dates and the years in between a historical relevancy.

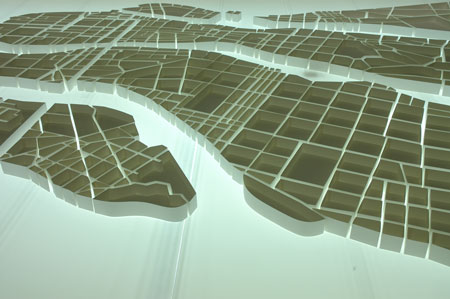

Hiroshima, 1930 consists of a massive 16—10ft. light box holding a 3D paper map of that city’s buildings and streets, 15 years before they were devastated by the Little Boy nuclear bomb. The installation brings to mind the modular and rectilinear sculptures of LeWitt or Smithson, but it is more reminiscent of a war room, a literal stage where buildings and the humans they house are envisioned as targets for future destruction. Even with this theatrical set up, the work comes across as surprisingly restrained, and instead of banging the viewer over the head with a moralizing tale of war and death, the piece calmly acts as a jumping-off point for a discussion of Hiroshima, before and after World War II, as an important historical site.

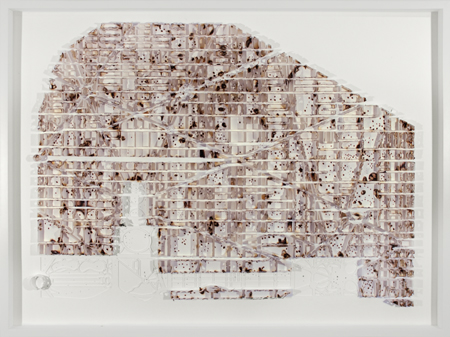

In another more startling work, Washington DC, Picton uses the same folded paper technique on a smaller scale, blocking out sections of The Capitol Mall and surrounding environs in a way that makes the layout unmistakable to anyone who has ever lived in, or visited, the city. This approximately 4—3 ft. work hangs in a white frame on the wall and is pockmarked with hundreds of seemingly random brown and black miniature explosions, places where the artist burned holes into the white paper. During the war of 1812 the British did in fact burn the White House and parts of the Mall, and riots have certainly set sections of the city ablaze in the past. But this diorama reads as a quick model for a Hollywood set explosion, a view of DC ravaged by aerial bombardment. While the work causes an immediate reaction regarding the possibility of DC in ashes, its spectacle nature and lack of historical grounding set it apart from other works in the show. While the work could be interpreted as an imagined future, juvenile wishful thinking, or misplaced Cassandra-like prognosticating, it seems more than anything to address our familiarity with seeing famous cities reduced to ashes in mass media.

With this we see the strength of Picton’s overarching project and the curious way he is able to incite viewers to plumb the feelings and associations that come with looking at a map, be it of the past or the possible future.